This year, I am teaching social studies for the first time in quite a while. That isn’t to say I haven’t been thinking about social studies. I have been studying it, talking about it, writing about it, in short, obsessing over it, for several years now. This obsession has taken the form of instructing at several Content Area Literacy Institutes for the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project, helping to author the Project’s new content area curriculum, presenting workshops on Writing in the Content Areas, and co-authoring Bringing History to Life with Lucy Calkins, part of the new Units of Study for Writing series. But all that aside, I had to wonder what would happen when I was charged with actually teaching social studies three times per week. Could I put all of my lofty ideas into practice?

These were some of the questions plaguing me as I sat in front of a blank google doc the other week, attempting to plan my first day. Where should I start? Should I be thinking about content (what my students need to know in order to start learning about Native Americans of New York State), or should I be thinking about constructs (what methods will best reach them one day one)? Then I remembered one of the most important principles of workshop teaching: begin by studying yourself as a reader and writer. Where would I begin a new study as a historian? Personally, I would start by reading about the big picture. But of course, workshop teaching is so much more than just asking students to do what we would do. We have to break down huge tasks into small, surmountable steps. I couldn’t just hand my students a book and say, “have at it”. Further, I couldn’t just model what kinds of books historians read, I had to model how historians read when they are just beginning a study. Often, historians read several texts on a broad topic in order to get a lay of the land. I decided there would be no better way to model this kind of reading than with a cross-text read-aloud.

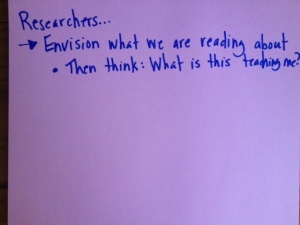

Richard Allington reminds us in What Really Matters for Struggling Readers that one of the top reasons readers abandon books is that they are not able to envision what is happening in the text. This is just as true for content area reading (the bulk of which is nonfiction) as it is for reading literature. So I decided to begin with a goal of bolstering students’ skill in envisioning, with a secondary goal of building background knowledge. I chose When the Shadbush Blooms by Carla Messinger with Susan Katz, a lovely picture book about a young present-day Lenape girl who connects with her past through the seasons, and The Iroquois: The Six Nations Confederacy by Mary Englar.

My teaching point:

I began with When the Shadbush Blooms, and modeled how I used the text to envision the actions and surroundings that the little girl was describing, then how I used what I was imagining to spur some thinking about what I was learning. Then, I guided students to try the same work, telling a partner what they were envisioning and what they were learning. At the end of the read aloud, I modeled for students how I put together some of the details we had learned – such as: the Lenape often ate what they grew or caught – to come up with larger ideas about what I was learning – such as: the Lenape have an important relationship with nature. I invited the students to talk in partnerships to try the same – putting together some of the details they had learned into larger concepts. Finally, I invited students to join each other in a whole-class conversation, sharing some of these ideas into the group. While students talked, I captured some of what I heard them saying in an idea web. (Side note: I decided to model this kind of note-taking as a way to plant the seeds for future note-taking experiences to come, more on that topic soon.)

Though I kept the conversation brief, as I found students’ stamina for whole-class conversation to be at about five minutes (for more on talk stamina, see my previous post), from this charting, the students and I were able to see how much real information they had gleaned from a picture book and a brief amount of discussion.

Next up: trying the same work with an informational text. I read few passages from The Iroquois by Englar, modeling and then inviting students to try the same strategy process as before. Of course, envisioning the text can be more difficult in an informational text. To support students in transferring this skill, I chose passages that were similar in content to some of the concepts that are explored in the picture book – for example, passages that described jobs of men and women, and ones that described ways in which the tribe gathered food.

We added some of the students’ new thinking to the web.

Finally, we compared the ideas we had come up with after reading the two texts, annotating similar categories and starring ideas that seemed particularly important.

A thoughtful (albiet brief) discussion ensued, about gender roles and how these might translate in the students’ own culture, and about the similarities between the two tribes’ approaches to living from the land. Students tried to imagine present-day New York as the place where Native American tribes such as the Lenape and Iroquois depended on the nature around them in order to survive, laying the groundwork for a concept that is central to the Unit of Study.

Some big ideas about cross-text read alouds:

- It is not necessary to read whole texts, or huge sections of texts. In fact, carefully chosen snippets of texts often work best. Researchers often read short excerpts of texts in conjunction with one another to corroborate what they are learning. It is perfectly acceptable to model how to do this with a read aloud.

- You can model several skills at once with a read aloud. Note-taking is a perfect skill to model in a cross-text content area read aloud. Keep in mind that a major purpose of read aloud is to model skills and strategies that are just beyond what students can do on their own.

- It’s not too early in the year to start with skills and strategies that feel lofty, such as reading across texts or taking notes in a web format. By modeling skills such as these early in the year, you are showing students that they are attainable, and you are also setting the groundwork for skill development along higher trajectories of learning.